Interview: The sound of Untitled Goose Game

Honk! Em Halberstadt and Nico Disseldorp discuss building a balanced soundscape.

Posted on October 21, 2019

In Untitled Goose Game, you play as a mischievous goose, free to explore a pleasant village and harass its inhabitants. Taking a fresh approach, the game is recognized for its humour, accessibility, and charisma.

The sound of Untitled Goose Game is integral to its appeal. From the distinctive honk of the goose, to the uncanny realism of physical objects and a curiously evolving score, the creators skillfully balance the chaos and comedy of the goose’s antics with moments of calm.

In this interview, sound designer Em Halberstadt and game developer Nico Disseldorp explain how they use sound to give the game its distinctive character.

Can you tell us a bit about your background? How did you end up working on this project?

Em: In the past I’ve dabbled in installation art and video editing. I was drawn towards game audio because I loved the idea of interactive audio, and the potential it had to affect stories. After Gord brought me on to A Shell in the Pit I was lucky enough to work on some projects that House House liked the sound of!

Nico: I’m from House House. We are a group of four people who were good friends for a while and then started making videogames together. We started making the goose game in late 2016, and brought Em on board about a year later after getting a publisher and some extra funding.

How many people worked on the audio? How was the team structured?

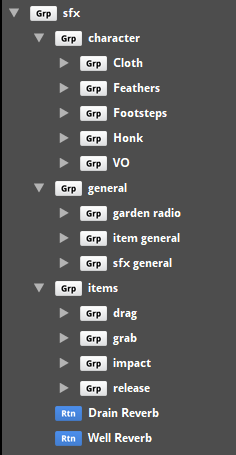

Em: I did the creation and implementation of the SFX. Nico was hooking up the events, so I worked with him the most. Nico, Jake, Michael, and Stuart [the House House team] all had lots of great ideas and feedback on the sounds. I also had help from Gord, Rachel, Nick, Millie and Joey of A Shell in the Pit with props and voice over. Dan [Golding] and House House created and implemented the music.

How did sound design fit into the overall design and production of this game? When did the development of the sound begin?

Nico: We started using placeholder sounds right from the get go. The goose’s honk was one of the most important parts of the game, and had to have audio. I think the honk went into the game in the first day or two. Another very early addition was the radio item, which added the first music to the game. For these placeholder sounds we used sound and music from royalty free sources, and played them using Unity audio. It was only after Em came on board that we started using FMOD.

Despite having a playful art style, sounds in Untitled Goose Game are quite realistic. How did you decide upon the sound design aesthetic for this game?

Em: This aesthetic just made sense with my style and with the game. Most of the sounds are props, and making them sound realistic was the best way to make you feel like you’re messing with real physical objects. I think since the humour of the goose is based in reality, having realistic sound helps to sell that.

At times, the game’s soundscape is quite minimalist. What was the intent behind this approach?

Em: Part of the intent was having space to relax and play around with all the objects outside of the times when the goose is wreaking havoc. I also think it’s funnier this way, because when you do decide to engage in chaotic behaviour there is more of a contrast in the soundscape. I think Dan and House House did a fantastic job with the music on this.

Nico: We didn’t implement the non-diegetic music until relatively late in production. By the time we were implementing it we could already tell that Em’s soundscapes were amazing, so we took care to make sure the music didn’t step on the rest of the soundscape’s toes. This meant leaving lots of periods without music.

Were sounds recorded in house? What was your workflow when developing sounds for the game?

Em: Almost all the sounds in the game were recorded. For most of the props I would write a list for each different level and pace around looking for various objects I could use. I would then record them in my backyard, dropping or dragging them on concrete, grass and wood surfaces. I’d then edit each prop into a few variations and add a velocity parameter in FMOD, which I would adjust in the mix phase.

How important was iterating on the sound design? Did you use the live update feature in FMOD?

Em: I used the live update feature a whole bunch. Most of the mix phase involved grabbing, dropping, and picking up every prop in the game over and over, so being able to adjust as I was doing this was pretty important.

How did you go about balancing the overall mix?

Em: I grouped sounds into their different categories and mixed based on what kind of sound they were first. I then adjusted from that balance based on the size of the prop. So all the grab and release sounds are at a reliable level, as well as the impact sounds. We wanted the honk to sit above most of the sounds, but still at a comfortable level.

The game has been highly praised for its adaptive music. What were the goals for this system?

Nico: The dynamic music was inspired by people’s misunderstanding of our original trailer. The trailer has its visuals cut around this very stop-start solo piano piece from Debussy’s Préludes. But perhaps due to the nature of the piece, people thought it worked the other way around - that the music was reacting to the game.

We optimistically decided to just try and make what people thought we were doing, to make this solo piano piece sound like it was reacting to the game live. We figured that we could use a bunch of different Préludes, but have them play in a way that made it seem like a live piano player was watching your game and playing along.

How did you choose the composition in terms of style and instrumentation?

Nico: We chose Debussy’s Préludes because they sound a bit like silent film music or the type of “Mickey Mousing” you hear in cartoons, without being too corny or familiar (to most people).

It’s fortunate that the Préludes are all solo piano. The dynamic music system probably wouldn’t have worked otherwise.

How did you approach building the adaptive elements of the music system?

Nico: Dan made two different versions of each piece (a high energy and low energy version) and then cut them into a number of smaller chunks. Then depending on the current action in the game, the music system can either play the next chunk of music in its high energy form, its low energy form, or to wait for a while before playing more music.

All of the music logic is done in code, and I call an FMOD event that corresponds with the chunk of music I need next.

Once we had this system working we realized that it could feel more responsive if the music was cut into smaller chunks, so Dan ended up splitting each piece into hundreds of different files each representing two beats of music.

Dragging objects across different surfaces impressively results in different sound textures. How was this implemented? What impact did this have on the player experience?

Em: I recorded each prop separately on each of the main surfaces in the various areas in the game. It ended up being a ton of work, but I like to put a lot of effort into details like this to help make the game feel as dynamic as possible. I thought it was important for the player to be able to find joy and get a little reward for every new little thing they tried. The dragging action was recorded by moving the props in circular patterns on the ground. I did end up using a general heavy or light drag sound for grass, water, and dirt unless it was a special prop that would sound unique on those surfaces.

Was there a standout feature of FMOD for implementation?

Em: Live update! It would have been tricky without it.

There are many subtle audio effects in the game. What’s a detail that you were particularly proud of?

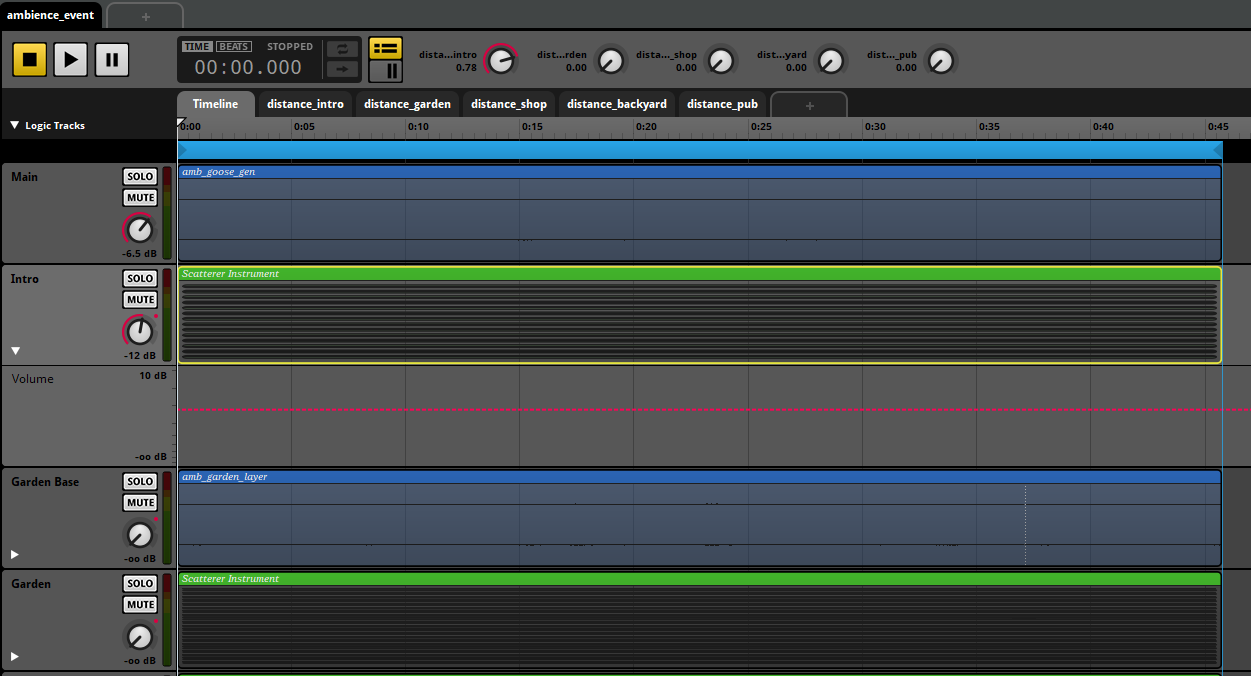

Em: It’s probably one of the most subtle aspects of the sound but I’m proud of the ambience system. I made sure each different area had a unique ambience with different birds, or less of a particular kind of bird, using scatter sounds. They’re more chirpy in the shop area, for example. Since it’s all one area, as you approach one section of the game a parameter will raise or lower the volume of each special layer.

Are there any final thoughts you’d like to share about the sound of Untitled Goose Game?

Em: I like to tell new sound designers coming into the industry that they don’t need to worry too much about getting fancy gear, plugins or libraries, and I think the sound of this game is a good example of how you can do a lot with very little. I mostly just used a microphone and portable recorder! (In terms of which gear, whatever you can afford will do. The main question to ask is, does it record sound?) I would like to share this idea because it’s a more accessible way to think about sound design. Being creative doesn’t have to mean being good at making cool synth sounds, it can also mean attaching a ball to a rubber spatula so it will sound like a mallet.

Explore for yourself

Untitled Goose Game uses FMOD for adaptive audio. Learn more about the workflow and get creative.